Italian names generator 🤌 (Part II)

Back to our series about generating Italian names! Last time we built n-gram models for our data, seen that results improve as n gets larger, but also discussed their limitations. In this post, we are going to define a measure of model goodness to quantitatively assess which n works best with the data we have.

The notebook reproducing the results shown in this post can be found here: github/leonardopetrini/learning-italian-names/likelihood.ipynb.

Introducing the likelihood

A very natural measure of how good is our generative model in reproducing the statistical properties of the data is the probability that such data was generated from the model in the first place.

Intuitively, if the data have structure, and our model was just randomly guessing, the probability that it generated the data would be very low, while a model correctly reproducing some data statistics (e.g. letter n often comes after letter i) would more likely have generated such data.

The measure of how likely some data \(\widetilde X = \{\widetilde x^i\}_{i=1}^m\) are, given a model \(\mathcal{M}\), is commonly called likelihood and is defined as,

\[P(\widetilde X\,\vert\, \mathcal{M}) = \prod_{i=1}^m P(\ \widetilde x^i\,\vert\, \mathcal{M}),\]where data points are assumed to be independent of each other (allowing to take the product) and identically distributed (allowing the same \(P\) for all samples). The larger the likelihood the better the model.

For convenience, we usually work with the log of this quantity. Moreover, we divide by the total number of samples \(m\) and add a negative sign. This is because:

- The likelihood can take very tiny values as it is the product of \(m\) numbers in \([0, 1]\), and \(m\) can be arbitrarily large. Taking the \(\log\) makes it more tractable. Also, the \(\log\) is monotonic, hence it does not change the argmax of this function with respect to the model’s parameters.

- The \(\frac{1}{m}\) makes it an average quantity over samples so that it takes reasonable values (\(\mathcal{O}(1)\)) and it does not depend on the dataset size (in physics, we would call the average log-likelihood and intensive quantity: a property of a system that does not depend on the system size).

- The negative sign makes it positive and bounded from below by zero. Also, it makes it interpretable as a cost function, a very common object in machine learning (ML).

To summarize, we define the average negative log-likelihood as

\begin{equation} \mathcal{L}(\mathcal{M}\,\vert\, \widetilde X) = -\frac{1}{m}\sum_{i=1}^m \log P(\ \widetilde x^i\,\vert\, \mathcal{M}) \label{eq:nll} \end{equation}

where the order of \(\widetilde X\) and \(\mathcal{M}\) is reversed in the log-likelihood as it is commonly seen as a function of the model, given the data.

This quantity is the cost function we aim at minimizing, and will support our choice of a model/set of parameters over another. In the following section, we’ll see how to make proper use of it!

Train, validate, test!

❓ What makes a good machine learning model?

In the previous post, we have discussed two properties we would like our generative model to have:

- Ability to generate reasonable examples that look like the training ones;

- Ability to generate new examples, i.e. different than the one used for training.

On the contrary, a model is bad if it generates examples that are reasonable but just copies of training samples. Or if it generates new examples that have nothing to do with the original ones (i.e. noise).

In ML jargon, a good machine learning model has good generalization capabilities. This means that model A is better than model B if, after training, model A has a lower log-likelihood on new samples that did not belong to the training data, but that ideally come from the same probability distrubution.

For this reason, we must evaluate the log-likelihood of our models on a different dataset than the one we have used for training.

In particular, a common pipeline is to randomly split the dataset at our disposition into three parts (say 80%, 10%, 10%), the training, validation and test sets. The first is the one used for training the model, the second is used to have a sense of the model generalization capabilities, and accordingly tune the model hyperparameters (e.g. the value of n in n-grams). Finally, the third must be only sparingly used, usually at the very end of our ML pipeline, to get an unbiased estimate of the model performance.

Splitting the dataset into three parts makes our ML pipeline more robust to overfitting, both with respect to the models’ parameters and to the manually-tuned model hyperparameters. We’ll see an example of overfitting below.

Likelihood and word models

Now we have all the tools to start playing with our beloved Italian names!

A toy example

As a warm-up, we introduce a toy words dataset with just three words:

\[\widetilde X = \{ab, bb, ba\}.\]As we previously discussed, each word will have an arbitrary number of leading special characters ".", and one trailing ".". In this case, the vocabulary of characters \(\{\cdot, a, b\}\) is of size L=3.

We split \(\widetilde X\) into a train and a test set (we don’t use validation as we will not tune hyperparameters at this stage, but just assess performance).

\[\widetilde X_\text{tr} = \{ab, bb\}, \qquad \widetilde X_\text{te} = \{ba\}.\]In fact, our generative models will make predictions for every character in the words \(y^i\), given the previous ones \(x^i\). Effectively, our dataset consists of nine tuples \({( x^i, y^i)}_{i=1}^N\)

\[X_\text{tr} = \{(\cdot,a), (\cdot a,b), (\cdot ab,\cdot), (\cdot,b), (\cdot b, b), (\cdot bb, \cdot)\}, \qquad X_\text{te} = \{(\cdot,b), (\cdot b, a), (\cdot ba, \cdot)\}.\]where the number of leading "." depends on the model. For example, 1-gram model we need no leading "." as no context is needed for predicting the leading characters in a word. The model would fit the train set

by counting the number of occurrences of each character in the vocabulary, and make a normalized probability out of it:

| \(P^{1\text{gram}}\) | \(\cdot\) | \(a\) | \(b\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(1/3\) | \(1/6\) | \(1/2\) |

For the 2-gram model of \(X_\text{tr}\) we need one leading "." to give the context for predicting the first character. The model consists of \(L^2=9\) numbers, the normalized counts of each tuple:

| \(P^{2\text{gram}}\) | \(\cdot\) | \(a\) | \(b\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(\cdot\) | \(0\) | \(1/2\) | \(1/2\) |

| \(a\) | \(0\) | \(0\) | \(1\) |

| \(b\) | \(2/3\) | \(0\) | \(1/3\) |

From the models, we can compute the train and test losses, \(\mathcal{L}(P^\text{ngram}\vert X_\text{tr/te})\), using Eq.\eqref{eq:nll}. We report the results in the table below, togheter with the 0-gram model corresponding to random guessing.

| \(\mathcal{L}\) | train | test |

|---|---|---|

| 0-gram | 1.10 | 1.10 |

| 1-gram | 1.01 | 1.19 |

| 2-gram | 0.55 | \(+\infty\) |

A few comments on the results:

- The 0-gram model has no information on the training data, hence its performance is the same on both splits. We can keep in mind the number 1.10 as a benchmark.

- The 1-gram model has learned something from the data, hence reducing its training loss w.r.t. random guessing. The large test loss, on the other side, is a first manifestation of overfitting.

- The 2-gram model has a significantly lower training loss. However, its test loss diverges. This is because there are tuples in the test set \(\{(b, a), (a, \cdot)\}\) to which the model assigns zero probability—since they were not present in the training set—making the log diverge.

One simple way to regularize this divergence is to introduce smoothing to our model. Smoothing consists in assigning a finite probability to all tuples, even if they are not present in the training set. This can be done by add one to all tuples countings, before producing the normalized probability. The resulting 2-gram model would be

| \(P^{2\text{gram}}\) | \(\cdot\) | \(a\) | \(b\) |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(\cdot\) | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.4 |

| \(a\) | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.5 |

| \(b\) | 0.5 | 0.17 | 0.33 |

And the resulting log-likelihoods read

| \(\mathcal{L}\) | train | test |

|---|---|---|

| 0-gram | 1.10 | 1.10 |

| 1-gram | 1.02 | 1.14 |

| 2-gram | 0.84 | 1.36 |

We hence eliminated the divergence and observe, as a general trend, that the training loss increased, while the test loss decreased. This is a common feature of regularization methods.

Back to Italian names

Now that we have a better sense of the game we are playing, we can go back to our more complicated Italian names dataset and decide which n-gram model works the best!

First, we randomly split our dataset into a training and a test set (90% / 10%).

Also, we have learned that some amount of smoothing is necessary, as we go to large n, to avoid the divergence of the log-likelihood.

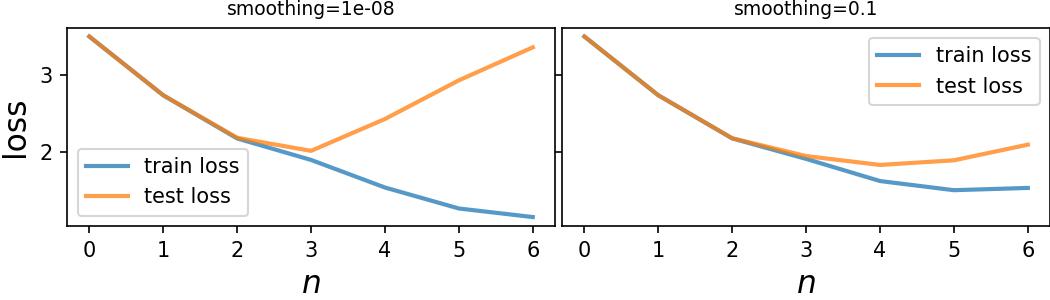

We can now compute the log-likelihoods for the two splits, for n-gram models of different order and smoothing values (see Figure below). The computations can be found in this jupyter notebook.

Some observations.

- Smoothing has little effect at small

n, while it largely mitigates overfitting for largen: the regularization effect we discussed above. - For small smoothing, the optimum is reached for

n=3,loss = 2.01. - Larger smoothing allows for a better optimum at

n=4,loss = 1.83.

Note: We should be careful with the smoothing parameter, as it gives a non-zero probability to n-tuples of characters that never occurr, which can result in very weird generated words.

Summary

In this post, we introduced a measure of model goodness that derives from simple notions of probability. By measuring the negative log-likelihood of n-gram models, we now have a quantitative way to assess their goodness. Interestingly enough, this is in line with the anecdotal observations we made in the previous post about 3-grams being a better model then 6-grams, as it produces fairly reasonable names, without just reproducing training set ones.

Now that we reached a good understanding of our problem: how to build simple models that capture data statistics, how to properly measure how good a model is, given the data, we are ready to dive in the realm of artificial neural networks 🧠!

Stay tuned. 📻