Italian names generator 🤌 (Part I)

This series of posts is largely inspired by Andrej Karpathy’s makemore. In my experience as an ML researcher, I’ve never found a more clear and sharp teacher than Andrej, his ability to walk you through the basics without being pedantic, and give insightful comments on the way, I find it unique. I highly recommend his (ongoing) YouTube series on Neural Networks: from Zero to Hero.

So, let’s start! As the title suggests, we are going to build generative models for Italian first names that will learn from examples. Such models will be able to generate new words from scratch or complete a series of characters. I will make use of two names datasets publicly available on GitHub:

-

names_1contains ~9k first names of people living in Italy, not necessarily strictly Italian. There are e.g. some French names; -

names_2contains ~1.7k first names.

Some examples from names_1,

ranuccio palmerio eustacchia quentalina gesuina azaea finaldo oriana

and names_2,

romoaldo donatella nicoletta aristeo natalia rainelda serafina susanna

In the following, I will consider the larger dataset, names_1.

The datasets, together with the notebook reproducing the results shown in this post can be found at github/leonardopetrini/learning-italian-names.

0-th order model: random guessing

Let’s start with the simplest thing we could do, and a very bad baseline: random guessing. I call it a 0th-order method because we give the model no information about the statistics of characters in the words. This point will become clearer later on when we go to higher order.

In this context, random guessing consists in taking a dictionary of all the characters that occur in our words dataset and sampling uniformly at random from them.

The dictionary of chars appearing in names_1 is the following

' ' 'a' 'b' 'c' 'd' 'e' 'f' 'g' 'h' 'i' 'j' 'k' 'l' 'm' 'n' 'o'

'p' 'q' 'r' 's' 't' 'u' 'v' 'w' 'x' 'y' 'z' 'à' 'è' 'ì' 'ò' 'ù'

You can notice that to the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet we added accented vowels, and the blank, as some Italian names are composite, for a total of 32 chars.

We add the char '.' to the dictionary as a placeholder indicating the word end, and append it to all words as well. This makes our dictionary of length L=33.

For generating a word, we will sample any one character uniformly at random (i.e. with probability \(1/L \approx 0.03\)), until we sample the special char '.', at which we stop. Samples from such a trivial model will look like this

hxdwsemlxermjùabpòctq gmamqqvz .

bcàennìqklrjktrhaulwtkwjjjmcj.

agt.

ùzfcdsùòdso.

.

ybtèò.

imìuopsgjzwmfekdqàyhèfl nlmìxsapcqyooòwwyòsfvnncfedcwmvvwthfemgsvipàohè vunxddàkfugmilùixvùccwìbtrtndòcùk.

zsyszqì.

ktmxktnsypd fxpks pagzsraàuyìytèjujjàiqwjpaqwè.

ptazvuwgisdpmfkzmjvyrgòlsnawòaddìtupnkysnakyxhòjhù.

Clearly not Italian, nor words! ❌

Indeed, one of the first things we notice is that words are incredibly longer than typical names. This is because the '.' will occur, on average, every 33 characters, making the average word length =33, much larger than the average word length in names_1 of 7.1.

We start to understand that the first necessary step is to account for the relative occurrence frequency of different characters.

1-st order model: average char occurrence

In this section, we start to learn from data. As hinted above, the 1st order statistics we can get from our dataset consist of accounting for how often each element in the vocabulary appears in Italian names.

To do so, we count how many times (N) each character appears. Then, we normalize the counting and obtain the probability p for char occurrence. These values are reported in the table below.

| space | a | b | c | d | e | f | g | h | i | j | k | l | m | n | o | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

N | 102 | 9116 | 792 | 1777 | 2628 | 5653 | 1345 | 1361 | 209 | 8380 | 50 | 38 | 4720 | 1979 | 5487 | 7585 |

p | 0.0014 | 0.1237 | 0.0107 | 0.0241 | 0.0357 | 0.0767 | 0.0183 | 0.0185 | 0.0028 | 0.1137 | 0.0007 | 0.0005 | 0.0641 | 0.0269 | 0.0745 | 0.1029 |

| p | q | r | s | t | u | v | w | x | y | z | à | è | ì | ò | ù | . | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

N | 709 | 73 | 4884 | 2147 | 2558 | 1141 | 997 | 65 | 9 | 26 | 721 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 9111 |

p | 0.0096 | 0.0010 | 0.0663 | 0.0291 | 0.0347 | 0.0155 | 0.0135 | 0.0009 | 0.0001 | 0.0004 | 0.0098 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.0000 | 0.0000 | 0.0001 | 0.1236 |

Notice that the special character "." appears 9111 times, which corresponds to the dataset size. Moreover, letters like j, k, w, x, y are very rare, while vowels are very common, except for the letter u.

Similarly to what we did for random guessing, we sample new words by sequentially sampling characters, this time accordingly to p, until we hit ".". Here some results,

io.

ttlfo.

iarf.

iefniaaieanie.

uiaahl.

lvpcoroniaadi.

rv o.

inrealo.

aoieueaneaa.

b.

Words length is now reasonable, and vowels appear much more often, as they should. Still, none of these words can be mistaken for an Italian name.

2-nd order model: pairwise correlations

Now we are starting to understand the game of incorporating data statistics into our model. In this step, we include 2nd order statistics, namely pairwise correlations between characters. This is to capture the fact that, e.g. the letter n often follows the letter i, o often follows n and so on…

Similarly to the above case, this is done by making a table of all possible character pairs, computing their occurrence N, and normalizing it to obtain a probability p. Then, we look at the current character, we go to the corresponding row of p and sample the next char accordingly.

Now you may ask: how do we choose the first character? To do that, we resort to a simple trick: we append to all words’ beginnings our special ".", similarly to what we did for word ends. In this way, the row of p corresponding to "." will tell us what’s the probability that a given name starts with any of the letters in the vocabulary.

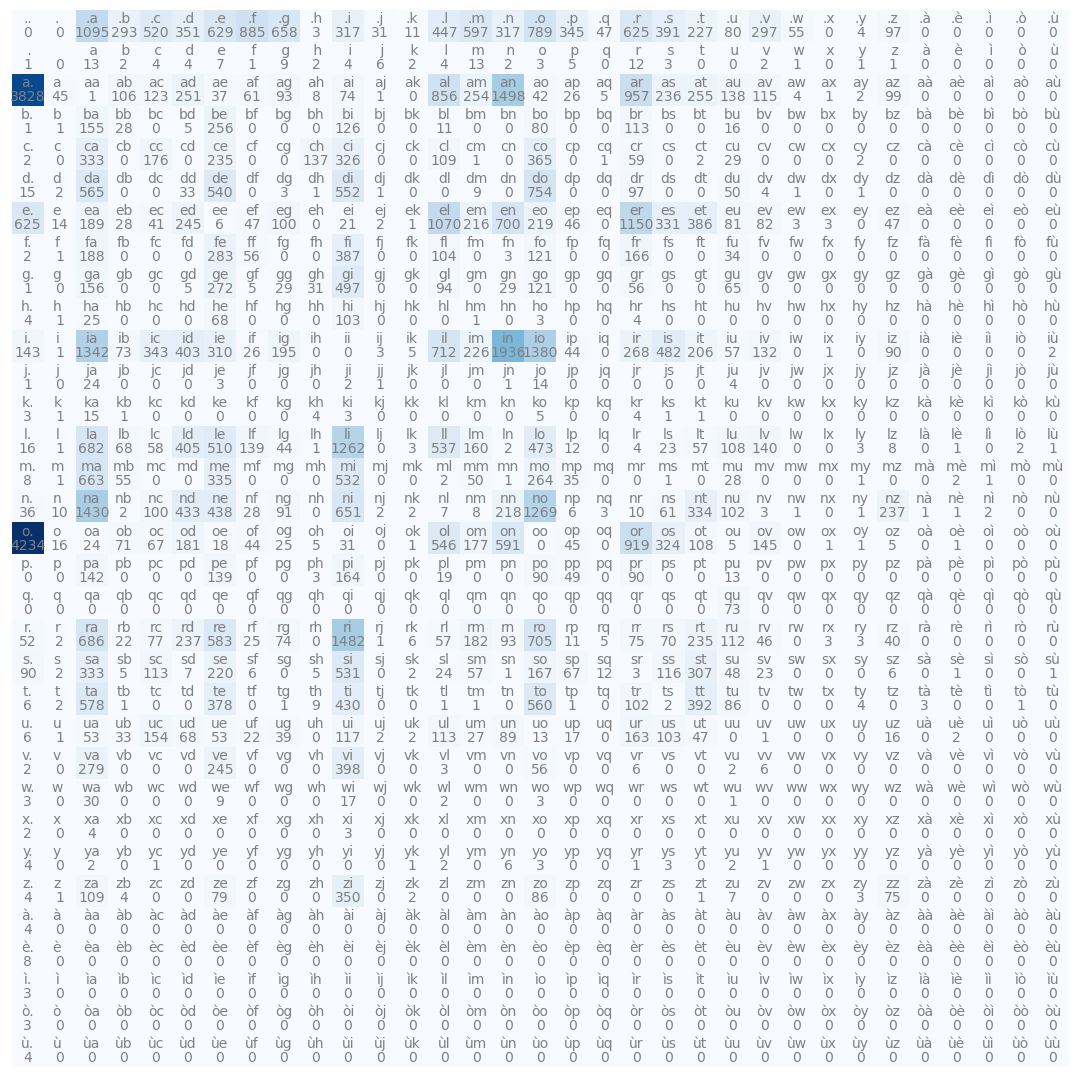

The table N for char pairs is shown in the figure.

Some features of Italian names start to emerge by looking at this table. In the 1st column, for example, we see that most names end with a or o, where the first is usually for feminine names, while the second is for masculine ones.

Taking a few samples from our model we obtain

vintona.

mada.

memefio.

o.

jalino.

ricaeto.

pelandinrazona.

wilio.

mia.

zia.

Start to sound reasonable, don’t they?!

Higher order models: n-grams

In the literature, the models we are introducing here are called n-grams, where n stands for the model order.

Note: How to sample from higher order models starts to be less intuitive, check the post scriptum below if you are interested in a more detailed walkthrough!

Better and better results can be obtained by going to higher and higher order correlations, for example, for n=3 we get,

vilommanna.

cennelforena.

dino.

do.

cantino.

edo.

lipetto.

curgio.

medazia.

rano.

❓ Could a non-native Italian speaker distinguish these from actual Italian names?

It looks like by just replicating 3-rd order statistics from data, our model does a pretty good job! 👊 Yet, n-grams have some limitations:

- Space. We need to store a matrix of size

L^n, withLas the vocabulary size. On my laptop, I can get at most ton=6before getting to a memory error. For larger vocabulary sizes, this limit is reached even earlier (e.g. for English sentences,L~10^4).

Here the n=6 results:

violanda. 1

emerigo. 1

cordelia. 1

mirco. 1

carolino. 1

arina. 1

azzurro. 1

fiolomea. 0

martano. 1

flamiana. 0

-

Overfitting. In these results, I appended a

1when the generated sample belongs to the original dataset. We see that the model learns by heart most of the examples and it can produce little variability beyond that. This is a manifestation of overfitting. -

Long-range context. When the average word length gets large (

>>n), n-grams fail to capture long-range correlations between characters.

Do modern artificial neural networks 🤖 overcome these limitations and give better results? Moreover, how do we decide if a model is better than another, beyond anecdotal evidence?

We will give answers to these questions in the following posts on this topic, stay tuned. 📻

PS: How to generate new words from the model

We briefly illustrate here how to generate new words given the model. We consider the case n=3. We built the matrix \(N(c_i, c_{i-1}, c_{i-2})\) by counting the occurrences of the three consecutive chars \(c_{i-2}c_{i-1}c_i\) in the data samples. Notice that all words in the dataset are now augmented with n-1 leading "." and 1 trailing ".". This is to capture the statistics of the first n-1 characters, which do not have n-1 predecessors.

We normalize the first dimension of \(N\) to obtain the conditional probability of a character given the previous n-1s,

Finally, to sample a new word, we make use of our special character ".". The first char is sampled according to \(c_1 \sim P(c \,\vert\, .\,,\, .\,).\) Then, we sample \(c_2\) from \(P(c \,\vert\, c_1,\, .\,)\), \(c_3\) from \(P(c \,\vert\, c_2, c_1)\) and so on, until we sample the stopping char ".". We got our new word \(c_1c_2\dots c_m\), where \(c_m = \,.\,\).